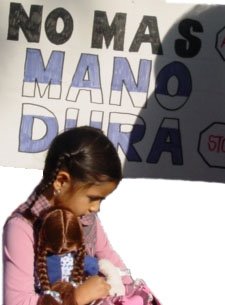

No más mano dura

There's good news and bad news about the sweeping civil gang injunction imposed on 6.6 square miles of Oxnard.

If you view the glass as half empty, the situation may look pretty grim. Litigation is likely to cost the county a fortune; citizens misidentified and harassed as gang members are outraged, insulted and intimidated; constitutional guarantees like freedom of association and freedom of expression are eroding; and, worst of all, our persistent epidemic of violence is being treated with a placebo of hot air about "urban terrorists" and a counterproductive bludgeon of "tough-on-crime" ideology hellbent on celebrating our national disgrace of shattering the world's record in per-capita incarceration.

The injunction hopes to achieve sweep-the-barrio incarceration of some 1,000-plus "John Does."

Today, young Oxnard Latinos can go to jail even for nonexistent "crimes" such as wearing a Dallas Cowboys T-shirt.

So what's the good news? Simply put, a grass-roots movement of violence prevention and rights protection has mobilized in powerful opposition to the injunction.

On the legal cutting edge of Oxnard's violence prevention movement, the Ventura County public defender is collaborating with pro bono attorneys to protect those served with the injunction and to address the troubling constitutional issues.

The judge, rather than compliantly issuing the blanket injunction that the district attorney pitched, has scheduled the case for January trial, denied a motion to expand it, and ordered mediation between community leaders and law enforcement.

At the same time, community activists who understand the root cause of street gang violence -- the failure to address marginalization at every critical juncture of a child and adolescent's life -- are educating public officials through demonstrations, neighborhood meetings and weekly appearances in City Council chambers.

New organizations such as Colonia Civil Rights Coalition and Chiques Community Coalition Organizing for Rights Education, Employment and Equity (CORE) have formed to help, rather than punish, at-risk youth before, during and after they get involved with la vida loca (the crazy life).

As a result of these organizing efforts, city and county officials have begun to take a second look at underfunded programs that are proved to reduce violence, like Oxnard College's KEYS Program for at-risk youth.

What the community activists understand is neither rocket science nor an assiduously guarded state secret. It is public knowledge, common sense and the hard science promoted and promulgated by the surgeon general, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health.

All those sources agree that youth violence must be addressed comprehensively by the entire "village" of healthcare professionals, educators, community activists, parents and survivors.

While popular media often delight in portraying gang youth as murderous scum beyond redemption, the profile of the gang banger is more typically a child hurt by racism and poverty, economically disadvantaged, learning-disabled, from a single-parent, immigrant home, or a succession of foster homes, where he or she may have been physically or sexually abused.

On the law-enforcement front, some Oxnard police officers are showing signs of understanding what Boston police chief Mickey Roache understood more than a decade ago when he participated in a community-based effort to reduce that city's juvenile murder rate to zero for the year 1996.

Chief Roache was honest and smart enough to publicly acknowledge, "You can give me all the police you want and build all the prison cells you can afford, but until you stop the flow of kids into violence, I cannot fix the problem."

Boston was successful because the experts viewed violence as a public health crisis, like tobacco addiction or automobile safety. The treatment included education, recreation, healthcare, substance-abuse rehabilitation, living-wage jobs, parenting workshops and psychological services.

To implement such a program, you don't need to build more prisons, criminalize freedom of association or enact draconian laws; you just need the compassion, creativity and commitment of concerned citizens like you and me.