The paradox of holy places: they exist—spatially, materially,—but they’re also all in your mind. And heart.

This is a reflection on our sacred space in the heart of Oxnard—Café on A.

On March 14, 1979, twenty-five years before I met Café on A co-creators Armando Vázquez and Debbie De Vries, a pre-dawn earthquake off the coast of Guerrero rumbled through Mexico City and destroyed much of the Iberoamericana Univeristy where I worked. Had it struck a couple of hours later, the campus would have been teeming with students, teachers and staff. Because of the fortuitous timing hundreds of people lived who would otherwise have died.

When I got off the subway and arrived on campus that afternoon, I was shocked by the devastation. My classroom had been reduced to rubble. But more than the material catastrophe, what I remember most vividly are the signs posted and painted on the walls that remained standing. Anonymous muralistas had gone to work immediately to bring forth image and poetry from the ruins.

One graffiti was seared into my brain forever: La universidad no es un edificio. The univeristy is not a building.

It was the perfect aphorism for the campus existential crisis. We read it and went about the work of sustaining what the university really was—a community. I like to think that no one who experienced the jolt of earthquake and poetry that day ever again confused a building with its meaning, existence with essence.

The Jesuit founders of the Universidad Iberoamericana knew something about sustaining institutions. The best among them knew the secret of sacred space: build it with your heart, your soul and your integrity, and it will last. Earthquake proof. Even if it all falls down.

Paradoxically, the institutions that are built in full consciousness that they are not (merely) buildings tend to be the most beautiful, the most soulfully imperishable. Build them of brick, steel, silver and gold; or build them of wind, sand, mud and straw. The materials don’t matter. The heart of the matter matters.

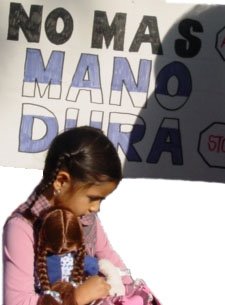

Debbie and Armando have designed our beloved Café on A as a sacred space that’s in a building, but not of a building. And thus Café on A becomes the molten core, the epicenter of a different kind of earthquake. The kind that shakes asunder the foundations of injustice, that inspires artists to rock our world, that releases underground tectonic energy to radiate in mystery and transform lives.

Café on A is exactly where it’s supposed to be: on Oxnard’s spiritual faultline, on the frontera, in the circle whose center is everywhere, whose circumference is nowhere.

Que dure mil años. May it last a thousand years.